2025 Public Health Laboratory Newsroom

Minn. Public Health Lab Uses High Tech Equipment to Detect Harmful Algae Blooms

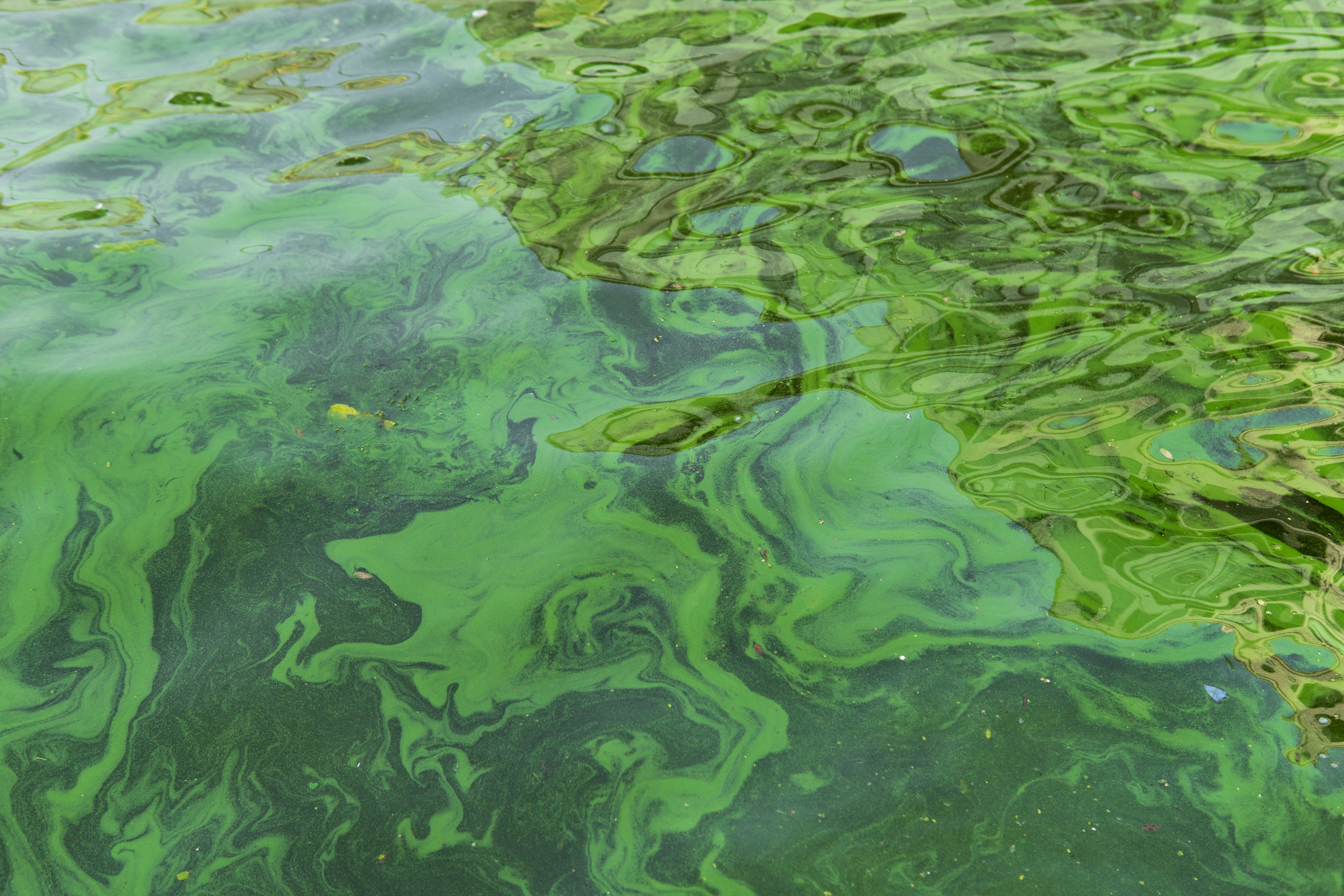

When you visit a lake in the summer, steer clear of areas of discolored water, foam, or scum. These could be what are known as “harmful algal blooms,” which can cause an illness with symptoms of:

- Rash

- Blisters

- Cough

- Wheezing

- Congestion

- Sore throat

- Earache

- Eye irritation

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Headache

Symptoms of harmful algal bloom-related illness usually begin around two days after exposure to the algae and last a few days in healthy people. You can get algal bloom-related illness by swallowing, being in contact with, or inhaling droplets of infected water. Pets are also susceptible to the illness.

If you are concerned you many have been infected, you can submit a report to the Minnesota Department of Health through the Reporting Suspects Foodborne and Waterborne Illness page.

What are harmful algal blooms?

Harmful algal blooms are populations of blue-green algae, which are technically not algae at all. “Blue-green algae” is another name for a group of bacteria known as cyanobacteria. Cyanobacteria have been mistaken for algae because they produce energy by photosynthesizing sunlight, as algae and plants do.

Harmful algal blooms are most common when temperatures are warm. Global warming is believed to be causing an increased spread throughout Minnesota, including some of species that were previously only seen in tropical climates.

Harmful algal blooms are most common when temperatures are warm. Global warming is believed to be causing an increased spread throughout Minnesota, including some of species that were previously only seen in tropical climates.

When cyanobacteria die, they can release toxins called cyanotoxins into the surrounding water. These cyanotoxins cause harmful algal bloom-related illness.

Unfortunately, by the time someone feels symptoms of harmful algal bloom-related illness, the algal bloom that caused it may already be gone. It is then too late to prevent others from getting sick. This is one reason why there are likely many more unreported cases of harmful algal bloom-related illness than there are confirmed cases.

Testing for harmful algal blooms

Many governmental agencies take a more proactive approach to preventing harmful algal bloom-related illness. Counties, parks and recreation boards, and the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency often take water samples from lakes and other bodies of water and submit them for testing for cyanotoxins. A program run by the Drinking Water Protection Section of the Minnesota Department of Health tests the drinking water of communities that get their drinking water from surface water, for these toxins before and after treatment.

These agencies send their samples to the Minnesota Public Health Laboratory, a division of the Minnesota Department of Health. Within the Public Health Laboratory, the Environmental Laboratory has specialized equipment and staff for analyzing water samples. The lab receives samples every week from Memorial Day to Labor Day and occasionally outside of summer months.

Few laboratories in Minnesota have the capacity to test for cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins, in part because it is a very labor-intensive process. Scientists must look at magnifications of samples in a microscope and count cyanobacteria by hand. There is newer technology that can automate this task, but few laboratories own it.

Few laboratories in Minnesota have the capacity to test for cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins, in part because it is a very labor-intensive process. Scientists must look at magnifications of samples in a microscope and count cyanobacteria by hand. There is newer technology that can automate this task, but few laboratories own it.

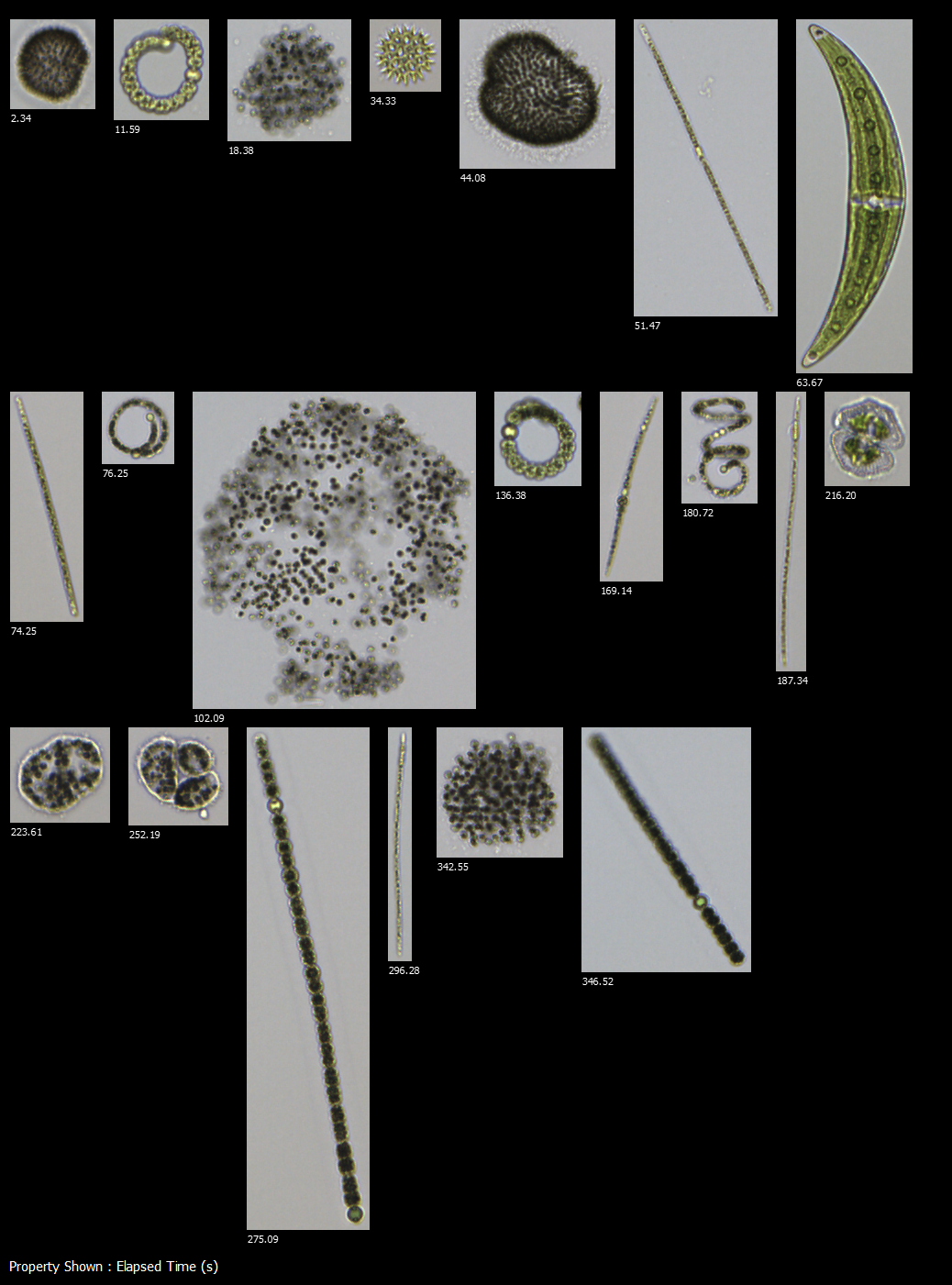

Even laboratories that do regularly test for cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins can take months to process samples, but the Public Health Laboratory has a much faster turnaround time. The lab recently acquired an instrument called the FlowCam 8000 that has accelerated testing dramatically. It now takes around 20 minutes to identify types of bacteria in a sample, work that takes a trained scientist 4 to 8 hours to complete without the instrument. The FlowCam 8000 also calculates the volume of bacteria in a sample, another time-consuming process for scientists.

The FlowCam 8000 is equipped with a laser that runs over particles as it passes through the instrument. The instrument takes a picture of a particle (see image, right) each time the laser detects a fluorescence at a particular wavelength. This produces libraries of pictures that scientists can look through to visually identify bacteria. The FlowCam 8000 learns from the classifications that scientists make, to automate classification of the types of bacteria in the sample using AI technology.

The investment in the FlowCam 8000 has already paid great dividends in allowing the Public Health Laboratory to improve cyanotoxin detection. Without it, the program to test drinking water for cyanotoxins might not be feasible. The laboratory is planning other improvements that will further strengthen its necessary work of protecting Minnesotans from harmful algal blooms.

Return to the 2025 Public Health Laboratory Newsroom.