2025 Public Health Laboratory Newsroom

Minn. Public Health Lab Helps Combat Rising Tuberculosis Rates

Tuberculosis is the leading infectious disease killer globally. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported 10.8 million people worldwide becoming ill in 2023 from tuberculosis and 1.25 million people dying from the disease.

While the number of reported tuberculosis cases in Minnesota has risen from 117 in 2020 to 194 in 2024, the disease remains much less of a threat in the United States than elsewhere in the world. The American health care system and the development of antibiotics in the 1950s have greatly reduced the impact of tuberculosis to those living in the United States.

While the number of reported tuberculosis cases in Minnesota has risen from 117 in 2020 to 194 in 2024, the disease remains much less of a threat in the United States than elsewhere in the world. The American health care system and the development of antibiotics in the 1950s have greatly reduced the impact of tuberculosis to those living in the United States.

In 1900, tuberculosis was the second leading cause of death among Americans, after only influenza and pneumonia. The number of deaths from tuberculosis declined rapidly after antibiotics were introduced in the 1940s, but it took decades to bring the disease under control. In 1953, 52.6 people out of every 100,000 still died from the disease in the United States. By 2022, only 0.2 out of every 100,000 Americans died from tuberculosis. (Source: CDC: TB Incidence and Mortality: 1953–2023.)

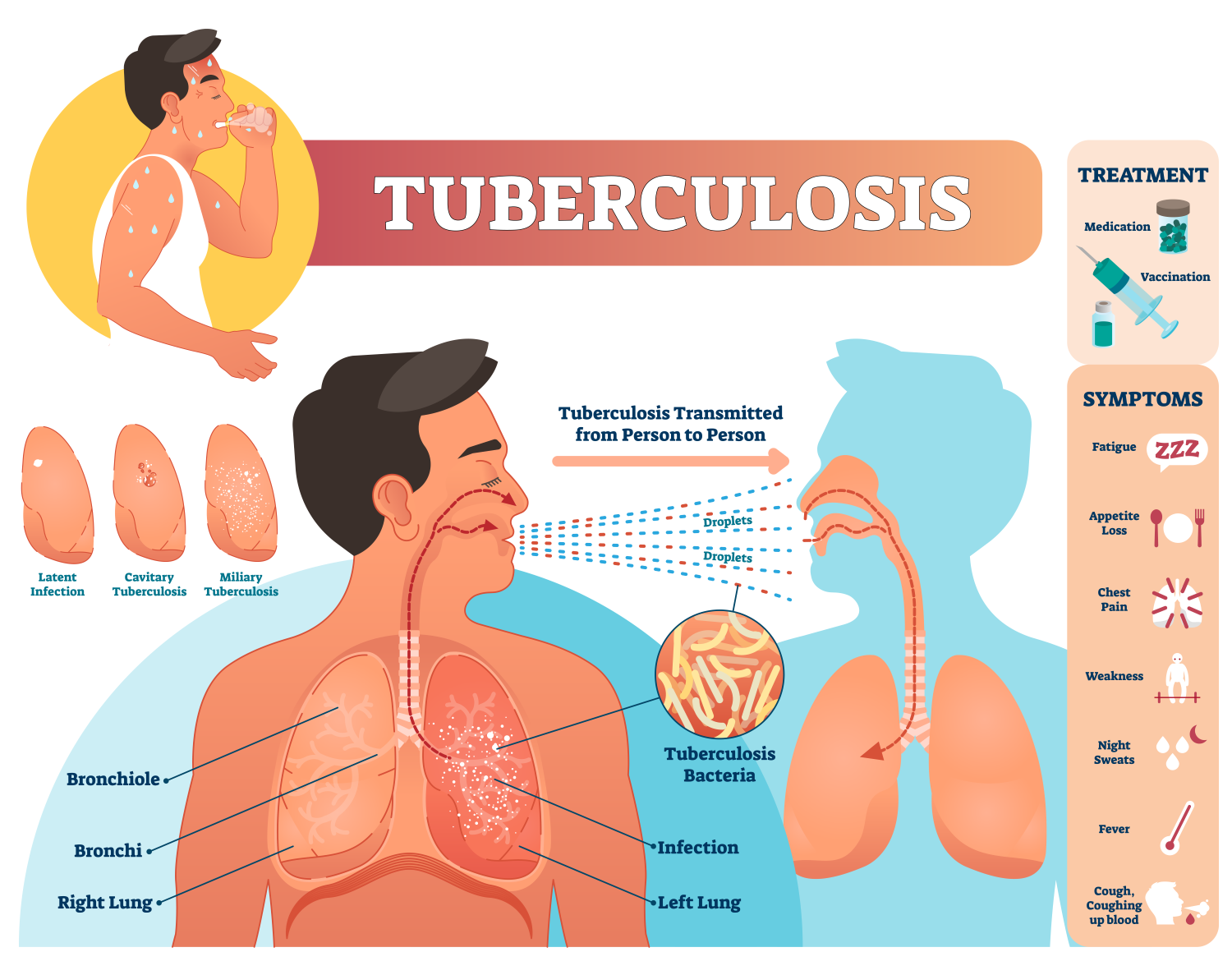

Many other diseases share this pattern of a precipitous drop in mortality rates over the 20th century, but most are viral infections that are being controlled by widespread vaccination. Tuberculosis is a bacterial infection for which there is no vaccine available that stops the transmission and development of the disease. In 1921, a vaccine called bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) was developed that reduced the severity of tuberculosis in infants and children. Today, BCG is widely used in countries in which tuberculosis is common to reduce childhood mortality. It is not generally used in countries like the United States that have relatively few cases.

How is tuberculosis diagnosed?

Tuberculosis is diagnosed in a few different ways. One is a culture-based lab test. A specimen from the lungs is put on special plates filled with nutrients for bacteria called agars. This process, called “culturing,” creates a larger sample of tuberculosis bacteria for scientists to test. Mycobacterium tuberculosis takes much longer to grow than most other bacteria, sometimes two or three weeks. There are also faster lab tests that can indicate in one day if tuberculosis DNA is in a lung specimen.

Only larger hospital-based or reference laboratories perform diagnosis of tuberculosis because it takes specialized expertise and extra safety measures to ensure lab scientists are not infected. Some such laboratories do only parts of the diagnostic work. The Minnesota Public Health Laboratory, a division of the Department of Health, performs all types of laboratory testing for tuberculosis diagnosis.

Active tuberculosis is on Minnesota’s list of reportable diseases. This means that if a Minnesota patient is suspected or confirmed to have active tuberculosis, the provider or lab is required to report the patient to the Minnesota Department of Health within one working day.

Hospital and clinic laboratories that identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis from a culture must submit an isolate to the Minnesota Public Health Laboratory. The lab’s scientists analyze the Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the sample to determine which antibiotics will combat it best, if the testing has not yet been performed.

Tuberculosis symptoms and spread

Tuberculosis was once known as “consumption” because it dramatically reduced people’s weight, as if they were being “consumed.” In the early 1900s there were no antibiotics or other effective treatment for the disease. People with tuberculosis were sent to sanatoriums for months or years to avoid infecting others.

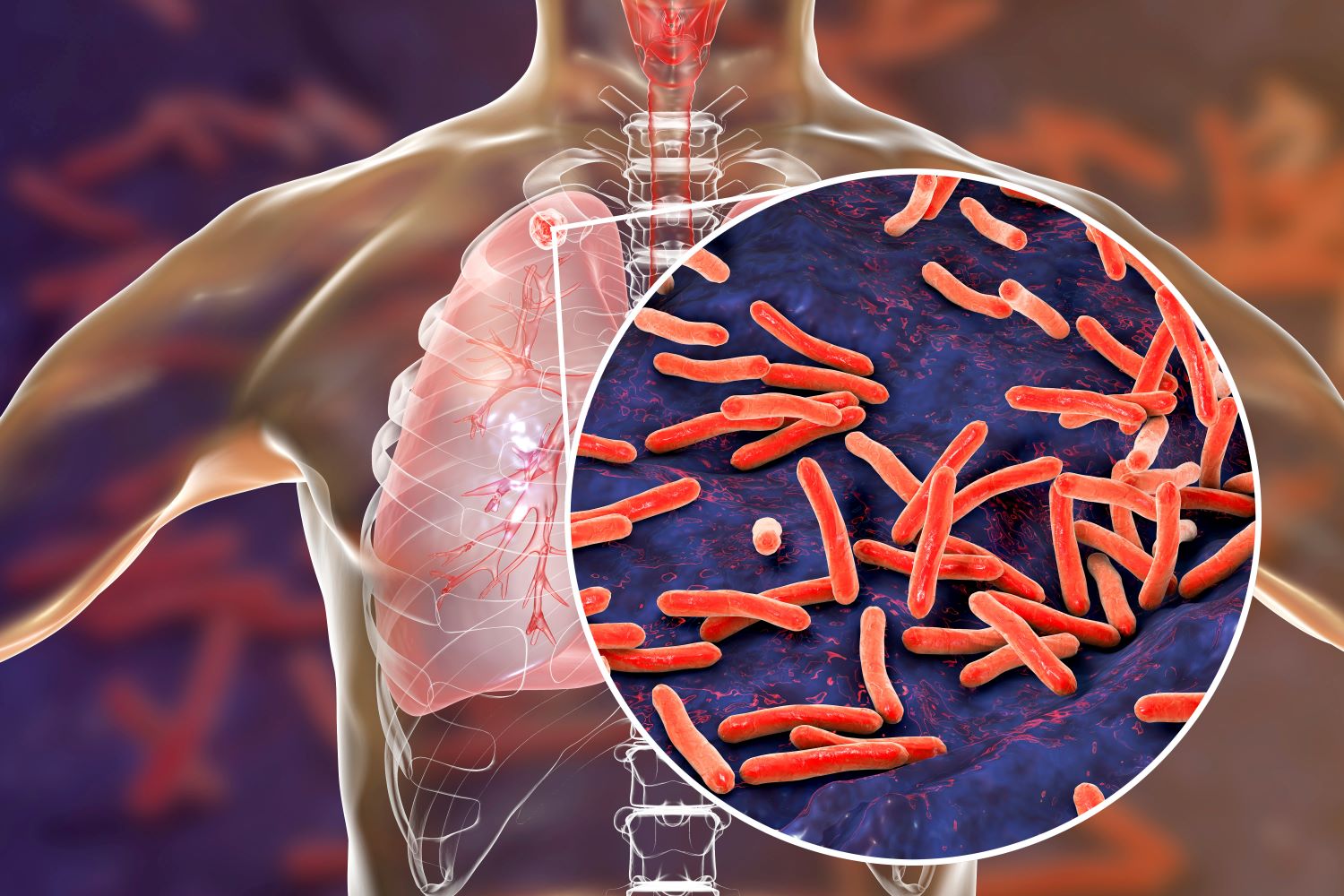

Tuberculosis can be anywhere in the body but usually affects the lungs and is spread through the air. One phase of the disease is called “latent tuberculosis infection,” in which infected people feel no symptoms. The bacteria that cause tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, can remain latent in a person’s body for decades. When tuberculosis is latent, it cannot spread to other people.

Tuberculosis can be anywhere in the body but usually affects the lungs and is spread through the air. One phase of the disease is called “latent tuberculosis infection,” in which infected people feel no symptoms. The bacteria that cause tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, can remain latent in a person’s body for decades. When tuberculosis is latent, it cannot spread to other people.

During the “active tuberculosis disease” phase, an infected person can spread it to others if the disease is affecting the lungs. In this phase, bacteria are reproducing and spreading throughout the body, causing tissue damage. Symptoms may include a cough lasting more than 3 weeks, weight loss, night sweats, and fever. An estimated 5-10% of people who are infected will develop active tuberculosis in their lifetime, but most likely within two years of becoming infected.

How is tuberculosis treated?

There are a number of very effective antibiotic medications for tuberculosis. However, treatment is complicated, and the Minnesota Department of Health has a large role in ensuring each infected person gets the optimal treatment plan.

Tuberculosis is a complicated disease that requires a long follow-up. People with active tuberculosis must continue to take medication for many months and check in with their physicians monthly after symptoms subside. Sometimes second- and third-line medications are necessary.

Because of these complications and the relative rarity of active tuberculosis, health care providers usually need help devising treatment plans for patients who are diagnosed with the disease. The tuberculosis experts in the Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Prevention and Control Division of the Minnesota Department of Health coordinate treatment of individual cases with hospitals and clinics. The Minnesota Public Health Laboratory also tests specimens from patients to monitor their responses to anti-tuberculosis therapy.

As with many diseases, treatment of tuberculosis is threatened by antibiotic-resistant organisms. Each year, nearly a half million people worldwide are diagnosed with a strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis that is resistant to frontline treatment. If these antibiotic-resistant strains become dominant, it would become much more difficult to treat tuberculosis and control its spread. Global and local public health systems are the first line of defense against antibiotic-resistant organisms.

Tracking tuberculosis outbreaks

The Minnesota Public Health Laboratory and the Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Prevention and Control Division work together to track outbreaks of tuberculosis in Minnesota. Because Mycobacterium tuberculosis may remain in people’s bodies for years before progressing to active tuberculosis, outbreaks can last longer than a year. At this writing, the most recent complete data is from 2024. Minnesota saw 194 newly reported cases of tuberculosis in 2024, up from 160 in 2023. This also represented an increase, from 132 cases in 2022. During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020, there were 117 newly reported cases.

The increase in tuberculosis case numbers over the past few years has been seen nationwide. Part of the reason is likely underreporting during the pandemic. Cases of COVID-19 were prioritized, and people with other diseases were less likely to seek treatment. Also, there may have been less transmission of tuberculosis because most people were wearing masks and avoiding close contact with others where possible.

Most cases of tuberculosis are identified only after people seek medical care for symptoms. However, a number of cases come to light because of the contact tracing done by local or tribal health departments in consultation with the Minnesota Department of Health. The health departments collaborate to identify people most at risk for active tuberculosis exposure and coordinate their evaluations. In 2024, 3% of those diagnosed with tuberculosis in Minnesota were identified through this contact tracing procedure.

Laboratory diagnosis of disease, contact tracing, tracking outbreaks, and assisting hospitals and clinics with treatment plans are all examples of the behind-the-scenes work that governmental public health institutions like the Minnesota Department of Health take on to keep once-dominant diseases like tuberculosis under control. The United States would be a more dangerous place if not for the close collaboration between our public health infrastructure and medical facilities.

Return to the 2025 Public Health Laboratory Newsroom.