Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Decommissioned Water Towers Not Forgotten

From the Summer 2025 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

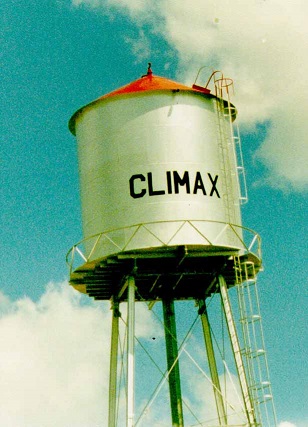

As of March 2025, 658 Minnesota community water systems (632 municipalities) have an elevated water tower with a total of 969 towers in the state. However, the ones not in use became the fascination of KARE-TV reporter Audrey Russo, who did a story on towers that no longer hold water but that have been embraced by townspeople, many of whom rally against efforts to tear them down. Shown above are examples of such towers, including Elk River, which was restored to its original colors of silver with a red top. The Milaca tower has been out of service for nearly 20 years but is still structurally sound and remains on the property of the old city hall, which is now the city museum. “Nobody wanted to see it go,” public works supervisor Gary Kirkeby said of the community reaction and desire to save it.

Russo also visited a still-in-service tower in Shakopee and interviewed water distribution supervisor Dave Hagen, who said the 1940 tower is the oldest single-pedestal, welded tower in the country. The tower was considered enough of an engineering marvel that it was featured in the December 1946 Popular Mechanics, which described it as “an unusual water tower shaped like a giant mushroom that rises 130 feet into the air. The shining ball atop the steel shaft is 43 feet in diameter.”

The KARE-11 story aired May 27, 2025, and can be found at 'They hold memories': Behind the push to preserve Minnesota's historic water towers.

Too Dear to Demolish: Historic Minnesota Water Towers

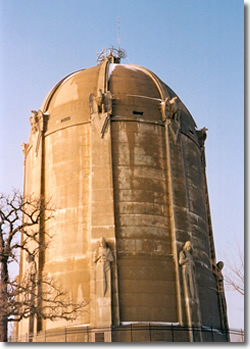

Minneapolis has three towers designated as city landmarks. The Kenwood tower, to the west of downtown, was built in 1910. The Prospect Park tower, off University Avenue in southeast Minneapolis, was built in 1913, and, two years later, the city purchased an existing water tower, the Washburn tower in an area known as Tangletown off 50th Street and Nicollet Avenue in south Minneapolis, and extended its height by 25 feet for additional pressure. The city increased the pressure even more in 1931 by demolishing the Washburn tower and building a new one. None is used for water storage anymore (the Washburn tower lasted the longest in its original function, holding water into the 2000s). Each tower is distinct. Prospect Park residents use the “witch’s hat” feature of their tower as a means to decorate the tower on Halloween. The Washburn tower has a number of adornments, including 16-foot-tall “guardians of health” mounted on pilasters, along with eagles at the base of the dome.

In 2013, as the water tower in downtown Osseo was approaching its 100th birthday, no longer containing water but serving as a familiar landmark, the city included an item in its newsletter, asking residents for feedback as it considered demolishing the tower.

Kathleen Gette, a proposal writer in her career, volunteered to write the grants to seek historic status for the tower, which would open doors for funding and help cover the costs to rehabilitate the iconic tower. Gette also started a “Save the Osseo Water Tower” Facebook group and collaborated with the Minnesota Historical Society’s State Historic Preservation Office. The efforts were successful. On June 5, 2017, the tower was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The familiar Ear of Corn water tower in Rochester received special status as the city’s Historic Preservation Commission voted unanimously in December 2023 to designate the tower as a historic structure. The Rochester city council approved the designation the following month.

The tower is 151 feet high and was built in 1931 by Reid, Murdoch and Company to supply its canning plant. The plant, last operated by Seneca Foods, has been demolished, but the tower lives on and is now owned by Olmsted County. A member of the preservation commission called it, “Rochester’s Eiffel Tower of Corn.”

Pipestone (left) and Brainerd (right) are concrete towers designed by the same architect, L. P. Wolff, around 1920. Pipestone’s 132-foot-high tower held water until 1976, when it was replaced by a larger new one. Brainerd’s tower, 141 feet high, was decommissioned in 1958 and has survived more than one threat to have it dismantled because the price of rehabilitation was considerably more than the cost of razing it.

However, both towers live on and are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Kasson and Ogilvie have water towers more than 100 years old.

Kasson’s 86-foot-high tower was built in 1895 and originally had a 2,000-gallon wooden tank, which was replaced with a metal tank a year later. The distinguishing feature is the base of limestone, which came from a quarry three miles north of Kasson.

The poured-in-place concrete cylinder in Ogilvie, built in 1918, is 80 feet high. The structure is topped by a parapet to make it resemble a medieval fortified tower. Ogilvie, then a village, was able to organize its first volunteer fire department with the tower providing the infrastructure to improve its water system. The tower held water until 2011.

St. Paul’s Highland 127-foot-high tower (on the left) held water until 2017, and the pump room in its basement is still in use. Completed in 1928, the tower was designed by Clarence Wigington, who was the first Black municipal architect in the country. Wigington worked for the city from 1915 to 1949 and designed a number of significant structures, including the Como Park Pavilion. The eight-sided tower rises on the second-highest of seven hills in St. Paul and has an observation deck that is open to visitors twice a year. On the right is a reinforced concrete tower built in 1924 on College Hill next to St. Mary’s Hospital in Rochester. Both towers are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Lindstrom saved its water tower after a new one was built in 1992, converting the old one to a coffee pot with the addition of a handle, spout, and knob. Initially, steam came out of the spout but was discontinued. However, the steam is returning in the summer of 2025, with a fog machine inside the tower emitting simulated steam twice a day.

One That Got Away

For years the Iron Range city of Eveleth labeled its towers not as Old and New, but rather as Hot and Cold, causing both residents and visitors to often ask if the temperatures varied in the two towers (it didn’t). Eventually the Old/Hot tower was dismantled with the Cold label removed from the existing one.

Of interest

Go to > top.